Tonight, quite unintentionally, I came across a familiar image. It filled me with memories and melancholy. But I smiled, too.

Tonight, quite unintentionally, I came across a familiar image. It filled me with memories and melancholy. But I smiled, too.

When I was finishing my doctorate, in law at Trinity College Dublin in 2000, I tried to get a lifelong friend over from my native Louisiana to direct a play. We’d collaborated in different ways when we were both studying at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. I was completing my law degree and he was doing graduate studies in drama. Both of us were easily distracted.

My friend and I had worked together on both his original work, as well as other slightly more conventional productions. I vividly remember his free-wheeling Going Going Gone, a very modern – and Southern – story deeply rooted in the classics he’d studied. I more vaguely recall long discussions about Sam Shepard’s Simpatico (1994). When we rearranged that script, with film-like editing and the deletion of some of the original text, he got into a little hot water.

We were also both fond of Irish drama for different reasons. At the time, he liked Conor Macpherson and Martin McDonagh, for the story-telling of the former and the dark comedy of the latter. I had closer links to Ireland and was a little more trad itional. I preferred, among others, Brian Friel and Tom Murphy. Friel’s Faith Healer (1979), Making History (1988), and especially Translations (1980) were masterpieces; he was also a terrific short story writer. Murphy’s Bailegangaire (1985) brought

itional. I preferred, among others, Brian Friel and Tom Murphy. Friel’s Faith Healer (1979), Making History (1988), and especially Translations (1980) were masterpieces; he was also a terrific short story writer. Murphy’s Bailegangaire (1985) brought

tears to my eyes. I daydreamed for years about directing it.

In any event, I don’t know how far my friend and I got in our discussions. In hindsight, it’s obvious that it was never going to happen. But before I’d realized that or come to terms with that, I’d begun to make some theater contacts. By the time that it was clear that my friend wasn’t going to be able to visit, and without him there to talk me out of it, I decided to go ahead and direct something myself.

Work on the play took at least six weeks, including a three week run in a small theater in Dublin’s Temple Bar. Work on my dissertation ground to a halt. The play went well, however, and we even broke even, despite the theft of some of the profits and a handful of my CDs. And I never told anybody – well, perhaps one person – that I’d never directed. I simply bluffed my way through.

As I see it, I was the best actor in the production …

The play was Horton Foote’s Tomorrow, itself rooted in a minor short story (1940) by William Faulkner. If Mississippi’s Faulkner is well-known, Texas’ Foote is, I believe, still underappreciated despite the fact that he won Academy Awards for adapting the screenplay to To Kill A Mockingbird (1962) and writing the screenplay for Tender Mercies (1983). He also won the Pulitzer for play-writing in 1995.

The play was Horton Foote’s Tomorrow, itself rooted in a minor short story (1940) by William Faulkner. If Mississippi’s Faulkner is well-known, Texas’ Foote is, I believe, still underappreciated despite the fact that he won Academy Awards for adapting the screenplay to To Kill A Mockingbird (1962) and writing the screenplay for Tender Mercies (1983). He also won the Pulitzer for play-writing in 1995.

Tomorrow had a strange life and took a circuitous journey before I worked on it. After Faulkner’s short story, Foote had adapted it for a teleplay (1960) in the days of live television. Later, he altered it for the stage (1968), though it seems to have been unsuccessful. Finally, he adapted the story for an independent film (1972) starring Robert Duvall. Duvall, a friend of the writer, was in both T0 Kill A Mockingbird and Tender Mercies, which echoed some of the themes from Tomorrow.

While I was made to feel foolish for doing so, I paid royalties to produce the play. But I did other things that weren’t as kosher. Don’t tell anyone, but while the royalties were paid for the stage script, I adapted my text and structure freely from the final screenplay. Conveniently for me, Foote’s various versions were already the subject of a book: DG Yellin and Marie Connors (eds), Tomorrow & Tomorrow & Tomorrow (1985).

Essentially, I tried to bring the depth of the film version – the best of the Tomorrows – to the stage. It wasn’t perfect. Even now, I regret not cutting a scene. I’d talked an actor – an older gentleman who was travelling into town for the production – into agreeing to be in a single scene in the play. Once he’d agreed, I didn’t have the heart to release him, though the play would’ve been better without it. We could have eliminated an intermission which broke the rhythm of the story.

At my most ambitious, I’d hoped to use a band in the production. This was something my friend, along with others, had already done successfully. And I found a wonderful trio – The Rough Deal String Band – that played authentic American music that broadly fit the time and place of  the story. But, quite understandably, they couldn’t commit to twenty-one performances. Instead, I used their music to create atmosphere before and after the play.

the story. But, quite understandably, they couldn’t commit to twenty-one performances. Instead, I used their music to create atmosphere before and after the play.

Again, just between us, I also used a traditional-sounding white gospel song that I’d written in a burst of song-writing activity before law school. I cringe now to think that it was entitled ‘Back to the Cross’ (though it wasn’t played for laughs). Worse, it was necessary for me to sing the song to one of the actresses so that she could perform it. We also added the (genuinely) traditional ‘All the Pretty Little Horses’ as a lullaby. And as the story was set in the rural South a century ago, I also had to coach the Irish actors to approximate rural Southern accents.

But I was very fortunate. The lead actor was brilliant and deeply committed. I think he eventually returned to teaching. The lead actress was perfect for the role. She was a friend, too, and, as I remember it, one of her next gigs was in the Irish film Evelyn (2002), a labor of love for Pierce Brosnan. She played Brosnan’s wife, a woman who abandoned him – he was then James Bond! – and their three children. Coincidentally, that film was directed by the same person – Bruce Beresford – who’d directed Tender Mercies.

Obviously, my friend had been given the film role when word of the play got out. Obviously. In fact, the reviews of the play were reasonably good. They’re around here somewhere. But I also remember words like ‘stately’ and ‘gravity’ being used in a manner that wasn’t entirely positive. Deleting that one scene would, I’m sure, have made all the difference. A different career would have beckoned …

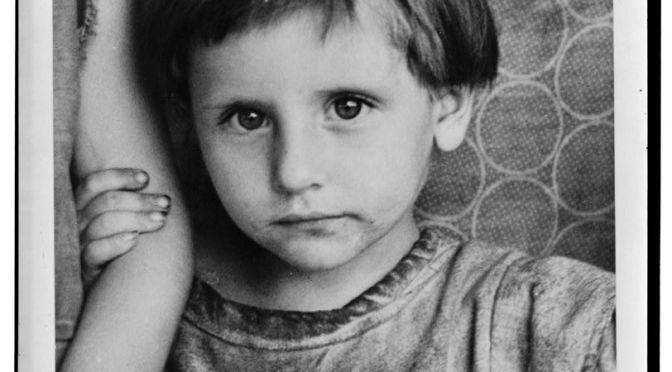

Anyway, to the picture. To help the stage designer do his work, I used a series of famous photos taken by the great Walker Evans, included in James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1936). And when a poster needed to be prepared for the play, the photo here was an obvious choice. While the real child was a girl, the play included a young boy who never actually appeared: at least not as I directed it. I won’t give anything away, but his absence was central to the story. Having the image made it easier for the audience to imagine him.

Anyway, to the picture. To help the stage designer do his work, I used a series of famous photos taken by the great Walker Evans, included in James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1936). And when a poster needed to be prepared for the play, the photo here was an obvious choice. While the real child was a girl, the play included a young boy who never actually appeared: at least not as I directed it. I won’t give anything away, but his absence was central to the story. Having the image made it easier for the audience to imagine him.

One last bit of trivia. The fellow who prepared the poster was a graphic designer who’d worked with U2. He and I also shared a love for old country music and then contemporary ‘alternative country’. We worked together on a little music magazine. I wrote the occasional article and review. And I was fortunate, too, to interview some interesting musicians: Ryan Adams, The Handsome Family, Joe Pernice, etc.

That poster’s on the wall next to me now, far not only from Louisiana, but Ireland as well, and far from family and friends in both. The photo reminded me of their absence, but also the time spent together. It reminds me especially of those that I’ve lost touch with over the years. I hope they’re well wherever they are.